Dapper Dan On Fashion Appropriation & Strategy Behind Gucci Partnership!

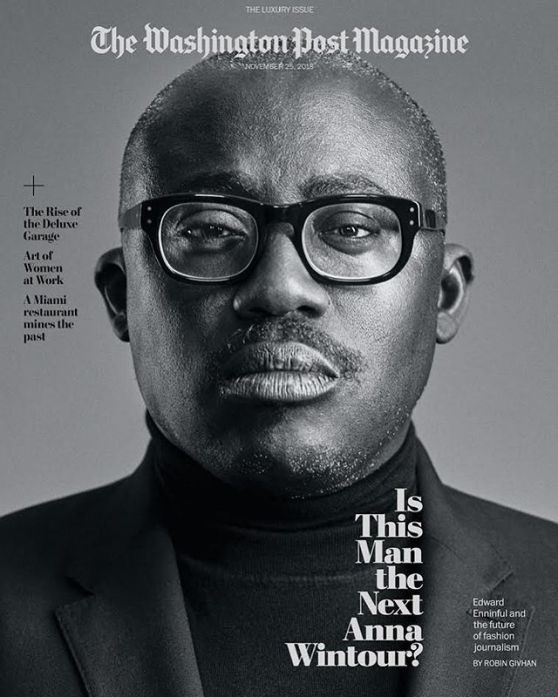

Edward Enninful, the new editor in chief of British Vogue, is supremely confident in both his aesthetic beliefs and in his worldview. In short order, he has upended a century-old publication, transforming its masthead to be more reflective of the global audience it seeks to serve and crafting some of the most memorable, inspiring and diverse fashion covers of the past year. His work exudes authenticity. He’s made inclusiveness look organic and effortless. And he’s made fashion look glorious.

Yet Enninful, on this day in the middle of Paris Fashion Week, is flummoxed over a coat. Not just any coat, Enninful tells me, but his coat. It’s caramel-colored, a gift from Riccardo Tisci, the recently appointed creative director of Burberry. The color has thrown Enninful thoroughly off balance. He prefers the strict camouflage of black and white: Black suit. White shirt. Black-framed eyeglasses. It’s his uniform.

The Burberry coat is a classic and looks splendid on Enninful, but he clearly does not feel fine in it. He’s chatting up his colleagues, killing time before the start of the umpteenth show of the day, and he’s clutching the coat around his torso with his shoulders hunched forward as if he’s attempting to vanish within its tailored confines. Most people would not have such strong feelings about a simple piece of outerwear, but Enninful has spent his entire adult life considering the way clothes not only make us look but also the way they make us feel. And the coat makes Enninful feel exposed at a time when he is in the spotlight as never before.

Enninful began his fashion career as a model, an instrument for telling fashion stories. Later, when he became a stylist, he selected the costumes for such narratives. As a fashion director for glossy publications, he was able to write the visual story itself. Now that he’s in charge of British Vogue, he has the power to determine whose stories are told at all.

“I always feel that the strongest stories resonate with the times we live in. So my stories will always be a bit social — they’ll have an edge,” Enninful tells me. “This is a time when the world is so divisive. So many walls are up. It’s so important that British Vogue just says, you know, it’s okay. It’s okay to show beauty.” It’s okay to highlight differences. “Diversity does work,” he adds with emphasis. “It’s okay.”

Edward Enninful, British Vogue’s editor in chief, outside the Miu Miu show during Paris Fashion Week in October. For many in the industry, his appointment came as a welcome surprise. (Jonas Gustavsson/MCV Photo for The Washington Post )

Enninful, 46, took the helm of the highly regarded British glossy in August 2017, marking a litany of firsts. Enninful is the first man to run the 102-year-old fashion magazine and its first black editor in chief. But those would be mere footnotes in his biography were it not for the singular perspective he brings to his work. He wants to celebrate art and creativity, of course. But he wants to do so in a way that feels both real and aspirational. He has been unabashed and vocal about the historical lack of diversity in British Vogue’s pages and on its staff, and he’s determined to remedy that specifically and within the fashion industry at large. “There’s such a buzz about him. Normally that subsides after the first couple of issues. You know people get over it and move on and look for the next thing. But I think they just find it so pleasing, and it’s working in every direction,” says veteran fashion editor Grace Coddington. “I love what he’s doing. I really do. … For me that’s the way magazines should look.”

Enninful’s take on globalism and his expansive view of culture have gotten him noticed. In the suddenly vigorous guessing game of who will one day succeed Anna Wintour, fashion’s most famous and powerful editor, Enninful is now top of mind. The corporate lords of Condé Nast, Vogue’s owner, have been adamant in batting away speculation that Wintour, 69, is stepping down or even slowing down anytime soon. “She is integral to the future of our company’s transformation and has agreed to work with me indefinitely in her role as [Vogue magazine] editor-in-chief and artistic director of Conde Nast,” said chief executive Bob Sauerberg in a statement this summer. Still.

The idea of Enninful as the next Anna Wintour — that is, the next editor to wield outsize influence within the fashion industry and to become iconic outside of it — does not require a move to New York and an office at One World Trade Center. That perch would give him a bigger audience and greater financial might. But he already has extraordinary influence. If Wintour is the producer of studio-financed, big-tent blockbusters, Enninful is the critically acclaimed indie filmmaker whose work punches you in the gut. It is rich and dynamic. It may rile you up or soothe you. It will make you think.

People also tend to forget that Wintour was not an omnipotent devil-clad-in-Prada when she climbed to the top of the American Vogue masthead 30 years ago. She grew into that role, and the kind of power she amassed reflected a fashion world that was becoming more corporate, more enamored with celebrities, more hierarchal.

American Vogue remains an advertising behemoth, but it has not been immune to the economic travails of magazines. The next Anna Wintour will rise out of an industry that is now more diffuse and deflated. It is a borderless business, one in which celebrities are just as likely to rise from social media and Nollywood as network television and Hollywood. The role of kingmaker is less important when a young designer can sell direct-to-consumer, broker a lucrative sneaker deal or court the affections of myriad influencers.

Enninful is well positioned for this new landscape. He has an extraordinary, artful eye that makes his work stand out amid the visual chaos. He regularly engages with his more than 855,000 followers on Instagram. He has his eyes set on Africa as a place to expand his readership and is traveling to Ghana this fall to advocate for arts education there. He’s well connected within fashion’s establishment and in the world of entertainment. He knows Oprah, for heaven’s sake. And he’s laser-focused on arguably fashion’s most pressing social issue of the day: diversity.

British Vogue’s December 2017 cover featuring Adwoa Aboah, and the September 2018 cover featuring Rihanna. (Courtesy of Condé Nast Britain)

For his inaugural issue of British Vogue, Enninful chose Adwoa Aboah as the December 2017 cover star. The biracial, British-Ghanaian model and activist has a honey-colored complexion, a sprinkling of freckles across her nose, the neck of a gazelle and a buzz cut. She is not especially long-limbed or lithe; she exudes solidity. On the cover, she wears a Marc Jacobs minidress in shades of pale pink and brown with a matching turban by the British milliner Stephen Jones. Her eyelids glitter with metallic turquoise shadow, and her lips shimmer in red. Aboah looks as though she has stepped from the 1970s by way of the 1940s. Her style borrows inspiration from the African diaspora while it revels in a slick disco glamour.

The image is a striking mix of references brought together by Enninful and photographed by Steven Meisel. It confidently rebuffs street style and informality. It is unapologetically high fashion — knowing, assured, refined. And yet it also says: All are welcome.

It was received with lusty applause in the British press, on social media and in the broader fashion world. The heightened enthusiasm was a reaction to the industry’s especially bleak record on inclusivity. When British Vogue’s outgoing editor, Alexandra Shulman, posed for a portrait with 54 members of her staff, the entire group was white. During Shulman’s 25-year tenure, there was a 12-year period when no black model appeared alone on the cover of the magazine. Until this year, no African American photographer had ever shot an American Vogue cover in its 125-year history. For more than 100 years, no black man or woman had ever served as editor in chief of any Condé Nast publication, until 2012 when Keija Minor became editor of Brides. A black woman has never won a Council of Fashion Designers of America award for menswear, womenswear or accessories. And in 2013, the international runways were so disproportionately white that Bethann Hardison, a former model agency owner and activist, with support from Iman and Naomi Campbell, published an online list of design houses whose actions they characterized as “racist” due to the lack of people of color in their fall shows.

Thomas Moorehead thought he had it all planned out: graduate from college, earn a master’s and doctorate degree and establish a career in education. He went on to accomplish three out of the four, by receiving his undergraduate degree from Grambling State University, his graduate degree from the University of Michigan, and teaching graduate students at the School of Social Work. However, one thing that he didn’t anticipate was to leave his PhD program to pursue a career in the automotive industry. This decision went on to become a risk worth taking, as he became the world’s first African American Rolls Royce Dealer in 2014, and now, a few years later, the first African American Lamborghini and McLaren Dealer in the United States.

After Moorehead spent two years working under his fraternity brother James Bradley (of Bradley Automotive Group), who offered to teach him everything he knew about the automative industry, Moorehead received training in General Motors’ Minority Dealer Development program and became an owner of a few Isuzu, Buick, and BMW dealerships. By 2002, Moorehead established Sterling Motors. As president and CEO, he has helped the company become the largest and leading luxury car retailer in Delaware, Southern Pennsylvania and the Washington Metropolitan area.

“Sometimes you have to take a step back in order to take a step forward. If you want to get in this business, you have to be willing to start at the bottom and work your way to the top…”

On top of being a successful businessman, Moorehead uses his platform to give back to the community and invest in the next generation. Along with his wife Joyce, Moorehead has provided over $400,000 in scholarships and emergency relief to high school students through their foundation for higher education, donated $100,000 to the National Museum of African American History and Culture, and contributed annually to Historically Black Colleges and Universities such as Grambling University, Bethune Cookman and Howard University.

“This is really what it’s all about, bringing other people up and giving something back.”

We couldn’t agree more! Thank you Mr. Moorehead for paying it forward and inspiring present and future African American entrepreneurs.

By Christine Hauser

December 12, 2018

The New York Times

An African-American man in a suit was handed car keys by someone who thought he was a parking attendant. A black lawyer was patted down by guards at a courthouse, even though his white colleagues entered without a search. An African-American politician was told she did not look like a legislator.

Such encounters are the plight of many people of color in the United States, highlighted in October when flight attendants questioned the credentials of a black doctor while she was trying to treat a passenger in distress.

When the physician, Fatima Cody Stanford, later explained that she always carries her medical license to help disarm skeptics in situations like the one she had experienced, other professionals said they, too, had developed strategies to brace themselves for people who will doubt them.

Those in professional fields historically dominated by white people, including law, medicine and politics, say that the pressure to be prepared for these moments can feel particularly acute. It affects how they dress, what they carry in their wallets and how they behave.

In interviews, about a dozen people described their efforts to ward off bias at work because they supposedly do not, as Dr. Stanford put it, “look the part.”

Ramon Ray, 46, a New Jersey entrepreneur, always dresses in a suit or a sweater. But he has still been asked by strangers to park a car, or been handed luggage or a coat to hang up. The bias, Mr. Ray said, was an assumption that he was “the help.”

He is also aware of the racist assumption that black men are menacing. It has prompted him to modify his behavior in ways that include keeping his distance from white female strangers, especially in isolated places like parking lots.

Black, Hispanic and Latino people make up a low proportion of medical school graduates in the United States. Several doctors described their experiences with implicit bias, or unconscious assumptions about race.

Dr. Ashley Denmark, 34, has overheard patients say they have not seen a doctor, even though she just examined them.

“I will go back, and round again, and say: ‘Hey, you didn’t remember seeing me? My notes are in the chart,’” Dr. Denmark said.

“It plays to a bigger problem that we have to normalize our presence in the field,” she added.

Dr. Mallory Whitley, 33, emphasizes to patients that she is their doctor. “I have been handed a tray before and asked if I am there to take their order,” she said. “If a nurse walks in — say, a white male — that is their doctor all of a sudden.”

She is also aware of how she delivers her orders. “I tend to not speak a certain way at work,” she said, “to make sure in other people’s eyes I am less menacing or less aggressive.”

It isn’t just black professionals. Hispanic and Latino people, Asian-Americans and people of other races have also reported encounters with bias.

Dr. Gricelda Gomez, 31, who is Latina, said she was helping herself to a supply of scrubs recently when an unfamiliar white nurse challenged her, assuming she was not a doctor and snatching her badge away after she did not provide her name.

“The default is never ‘you are the physician,’” Dr. Gomez said.

Such assumptions that she is less qualified than other professionals are rarely overt, she added. “This is the tricky thing about bias and talking about it,” she said. “It is not macroscopic anymore. It is all underlying.”

After the encounter with the nurse, she stopped wearing the badge that identifies her as a doctor on her hip and started displaying it more prominently.

“I pin it right in the middle of the V-neck,” she said.

Dr. Gomez, who also recalled being accused by a colleague of playing the “minority card” to get into Harvard Medical School, said she worked twice as hard to be perceived as competent as her white colleagues.

“The default is ‘Oh, she is Latina — she squeezed by because she is a minority,’” she said.

Anthony Denmark, 33, a lawyer in South Carolina, said he avoided wearing informal clothing on his firm’s casual Fridays.

Mr. Denmark, who is married to Dr. Denmark, has been patted down at courthouses where white colleagues walked in without a search, he said. In his car, he hangs work badges from the rearview mirror so he will always have identification within reach.

“At times I have had to show my license to my own clients before they believed that I was the attorney working on their case,” he said.

Kyle Strickland, an analyst at the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity, said, “I want to be able to say people should not have to wear a suit to fit in.”

“But at the end of the day,” he added, “you are still a person of color in America, because we have not necessarily confronted the issue of race head-on.”

In 2016, a black Ohio state legislator, Emilia Strong Sykes, 32, asked why she had been singled out for a search entering the Statehouse. “Well, you don’t look like a legislator,” she recalled the guard saying. After a pause, he said she looked “too young.”

Ms. Sykes braces for such encounters. She dresses conservatively, keeping her badge visible and unfailingly displaying her legislative pin. “I am very mindful of it,” she said. “You don’t want to be the black legislator causing trouble.”

She has also instructed her aide to greet visitors at her office entrance, so there is no question that the black woman they encounter sitting at the representative’s desk is, in fact, the legislator herself.

“There is something that triggers those thoughts that ‘she is not supposed to be there,’” Ms. Sykes said.

Rahmah Abdulaleem, 43, a Muslim lawyer, said her evolving head scarf choices reflected her efforts to pre-empt bias. When she was starting her career in Georgia, she would wear a dark scarf, making the Islamic covering less jarring for clients or colleagues. As she became more established, she started to wear colors.

“It was for them to be comfortable,” she said. “Then I finally got to the point where: ‘This is not me. I am not happy.’”

But she still recalls clearly how a colleague told her, almost 20 years ago, that she needed to “tone it down so people will feel comfortable.”

“And that sticks with me,” Ms. Abdulaleem said. “I make sure that I am not the loud black woman. I want to be respected for what is coming out of my mouth, and not falling into a stereotype in their mind.”

I’ve been quite lucky that since the age of nine I’ve always knew I wanted to be in fashion. It all started with a friend from school, we started designing clothes and our first company was called AK Clothing. For a short while I wanted to be a gymnast, but that’s didn’t last long.

I never wanted to go to university. At the time I was looking, most fashion universities focused more on design rather than the making and production of actual garments. I wanted to leave school at 16 and go and do an apprenticeship but my parents wanted me to stay on school. So, I did my A-Levels and then after college I did a pre-bespoke tailoring course at Newham College. From there I completed my training on Savile Row at the Savile Row Academy at Maurice Sedwells. Some of the best years in my career. After graduating – still knowing I wanted to own my own business, I thought it was wise to go and work at a fashion house to gain the experience. I needed get to know the industry, build contacts etc. So, I became a studio assistant and a cutter for a couture company, which at the time was based on Beauchamp place in Knightsbridge.

Your absolutely right! Savile Row has always been synonymous with men’s tailoring. In women’s wear there is more creativity with designing garments and I have always loved the aspect of bespoke and couture. At that time in 2013 there were very few female tailors on the row learning the craft, so it was daring for a female to launch a tailoring company, let alone become a tailor for a Savile Row house. So, me being the type of person I am, I said to my professor, “I could launch a women’s only tailoring house”. Which had never been done before. He thought I was bonkers but said it would be successful as it was something new and fresh!

Your absolutely right! Savile Row has always been synonymous with men’s tailoring. In women’s wear there is more creativity with designing garments and I have always loved the aspect of bespoke and couture. At that time in 2013 there were very few female tailors on the row learning the craft, so it was daring for a female to launch a tailoring company, let alone become a tailor for a Savile Row house. So, me being the type of person I am, I said to my professor, “I could launch a women’s only tailoring house”. Which had never been done before. He thought I was bonkers but said it would be successful as it was something new and fresh!

Oh many times! I would say especially when I came to a crossroads in my business and I was unsure of the next business move. It was quite challenging. I think when you try to do everything yourself and don’t share the journey with others it can be lonely when it comes to making sound business decisions. At that time, I knew it was time to start building a strong team. With individuals who had an extensive range of experience and who believed in my brand. My business mentor is a great calming influence. He has a wealth of knowledge and experience as he is a fashion investor himself. So he knows how the industry works. The ups and downs that the industry faces. So support systems like that really do keep you going when things become challenging.

Haha! I would love to say I am fearless. I was 24 when I started the company and at that time I was very fearless. I wanted a business, I started it and didn’t look back. I think if I had started the company now 4/5 years on, I probably would be a little more couscous in the decisions I made. I think the trick is when you want to do something that can be life changing, is not to think about it too much and hold on to faith and leap! We are all humans and sometimes we can talk ourselves out of situations or career choices because we think about it too much. Then the fear factor kicks in.When I face fearful moments I do take some time to sit and think about it. I always only share with those who believe in what I do and ones that will give you sound advice as they can also be the ones who propel you forward into doing what you want!

Who or what are your inspirations and why?

Who or what are your inspirations and why?In terms of the “Who” my mother is a huge inspiration. She is a very strong woman and I have seen her mentor other business women who now have very successful careers. Fashion houses – got to love Ralph and Russo. I met Tamara when they were based in Mortlake before moving to Mayfair and she is so humble and open. I absolutely love the brand they both have now built into a 9 figure amount.

Ohhh interesting question. When I started I would definitely say creative as I was always designing and making. I think now, as I expand the business and my team grows I have heavier responsibilities than I would before which require a more forceful approach in business. I now can’t sit at my desk and design as much or sit at my machine and sew. It’s my job now to make sure I am always driving in new business, new customers, sales are increasing, the brand is heading in the right direction. Our marketing message is on point, make sure salaries are paid – there is a lot to juggle. So I would say now…. a business women. The transition has been a real journey and I feel like I have grown and developed as an individual and I am sure I will continue to do so.

When I started I focused on bespoke only. Making one off pieces for clients. Two years later I launched into ready to wear with financial help from a good friend of mine which was very kind of him. This allowed me to create a full collection which I got into 4 stores. But like all businesses you have to be thinking ahead which I never did at the beginning. So I went from S/S and A/W to simply “named” collections which I could launch as and when I felt like it. Not necessarily because the industry dictated it. The fashion calendar is changing so many designers are launching when it suits them and when they feel is the right time. So many brands now launch new pieces every two weeks to keep up with the demand of the consumer.

“Hire people that are more experienced than yourself! “ And I couldn’t agree more. I think my generation are so stuck on wanting success fast and having a youthful company which I totally understand. Training the next generation is the future; we bring fresh ideas, a new take on things. We are more fearless than the generation before. But nothing is as good as experience. I have been in the industry for 12 years and hiring a skilled team that have double the amount of years on you is great because there is always something that I can learn from them.

Short term goals are to make sure all the foundations are set. There are 2 roles in which I need to add and making sure we have the right systems in place. Expand our market share by expanding our product range.

Mid term goals 6 months plus – drive business forward by gaining more business through collaborations and partnerships. Which will allow us to invest more into our marketing.

Long term – Open our first flagship store in the UK and begin to expand overseas in the US and Europe first.

One of my favorite books is “The Rockefeller Habits” by Verne Harnish. It’s a brilliant book and talks about the priorities and systems all businesses need to have to create a highly successful company. I have used this book as an inspiration to create a management style that works for me. So every Monday at 8:30am I have a management leadership conference call with my operations team which consists of 5 of us where we look at what the main goals are the that quarter and then we break it down month by month then week by week. Following I have a production meeting with my girls to talk about what clients we are making for and then financial calls with my account. I have designed an internal system where I post updates of what’s happening internally and externally in the business where the whole team can read in their leisure. I personally think it’s really important to keep your team engaged and inspired about what’s to come. So a few good systems we have in place and I am sure more will develop as time goes on.

I would say firstly build your support network and develop relationships. From mentors, entrepreneurs, investors and network as much as you can. Everywhere you go try and build those strong relationships as you never know when you will need to call upon them.

Find someone who you like the route they have taken in the industry and reach out to them for guidance – people are always willing to help you if you are genuine.

Develop a plan on the type of designer you want to be and why. Where you want to take the business. One thing I learnt from my mentor is developing a time plan which funny enough started out on a napkin which I still have today.

And most importantly – Listen. Be humble, don’t think you know it all. Take constructive criticism gracefully and learn about the industry. Self education is the best power tool. I think if you want to be successful in business you have to have a genuine interest in it. Learn what makes other brands successful, how they do it and why.

Thank you Karen

With the mega-success of Black Panther, Michael B. Jordan has suddenly become one of the world’s biggest leading men. Quite an achievement, sure, but the aspiring mogul is aiming way, way higher than mere movie star.

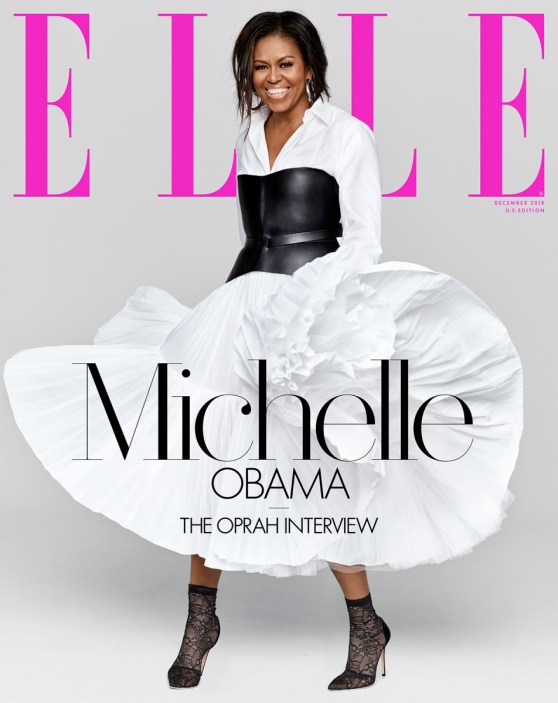

MICHELLE OBAMA – OUR FOREVER FIRST LADY

First Lady Michelle Obama graces the December 2018 Cover of Elle Magazine, as she takes off on a national tour to talk to America, and to promote her new book simply entitled, “Becoming Michelle Obama”. If the Robin Roberts interview was any indication, it seems like it will be an incredible read.

I’m still dreaming about that Michelle Obama/Kamala Harris run for 2020, but would settle for a Joe Biden/Michelle Obama ticket as well.

I just can’t get enough of our girl Chelle, from the south side of Chicago.

“NOW THAT’S FIRST LADY STYLE!”

Hump